by Doug Scott, MA, MSW, LCSW1

Introduction

For over two decades, I have walked alongside individuals seeking to understand themselves more deeply and navigate their spiritual journeys with greater awareness. As a psychospiritual therapist since 2001, my work has focused on integrating psychological insights with spiritual wisdom to create pathways for authentic transformation. My approach, deeply influenced by the teachings of Franciscan priest Richard Rohr, OFM, has evolved into a framework I call the “Tripolar Self”—comprising the Anchored Self, the Floating Self, and the Significant Self. This framework builds upon and integrates Rohr’s teachings on the True Self/False Self with the perennial wisdom of the Law of Three—a pattern of transformation that appears across spiritual traditions.

Brief Bio

I grew up in Keller, Texas, and attended the University of North Texas (UNT) where I studied Psychology and Spanish. During my sophomore year in college, I studied abroad at ITESM in Monterrey, Mexico. After UNT, I served as an international volunteer in Bluefields, Nicaragua, with the Capuchin Franciscans for two very formative years. Returning from Nicaragua, I worked at a non-profit organization in Worcester, MA, before going to graduate school at Boston College. I graduated from BC in 2004 with a master’s degree in clinical social work and a master’s degree in pastoral ministry. Since 2001, I have worked as a mental health counselor to English and Spanish speaking individuals, couples, and families.

My professional path began with training in traditional psychotherapy, but I quickly recognized that conventional approaches often neglected the spiritual dimension of human experience. This realization led me to pursue integrated modalities that honor both psychological development and spiritual growth. Since establishing my practice, I have worked with hundreds of clients seeking to reconcile their inner conflicts, heal from trauma, and discover their authentic selves.2

Richard Rohr, OFM, has been a significant influence in my life and work—a spiritual father and mentor whose wisdom has shaped my understanding of transformation. Rohr, a Franciscan friar, internationally known speaker, and founder of the Center for Action and Contemplation in Albuquerque, New Mexico, has dedicated his life to teaching contemplative practice and spiritual wisdom across traditions.3 His writings on the True Self and False Self particularly resonated with my clinical observations, prompting me to develop a framework that could bridge spiritual concepts with psychological realities.

Understanding the Law of Three

Before exploring the Tripolar Self, it’s important to understand the Law of Three—a principle that illuminates how transformation occurs in all living systems. This law, explored extensively in perennial wisdom traditions, recognizes that genuine development happens not through binary opposition but through a ternary process involving three essential phases: contrast, tension, and resolution.

The Three Essential Phases

Contrast occurs when we encounter difference or opposition. This might be the difference between what we know and what we need to learn, between our perspective and another’s viewpoint, or between who we believe ourselves to be and a deeper reality. Contrast is not a problem to be solved but the necessary starting point for growth.

Tension emerges when contrasting elements interact, creating dynamic energy. This is not negative; it’s potential energy, like a stretched rubber band containing possibility for movement and change. Tension manifests as the discomfort of not understanding something yet, the friction that arises when different viewpoints encounter each other, or the pressure felt when our current self-concept is challenged.

Resolution happens when tension transforms into a new synthesis that transcends the original opposition. This isn’t about one side “winning” or compromising but about the emergence of something genuinely new that couldn’t exist without the preceding contrast and tension. Resolution presents a choice: we can either maintain our current level of development (the horizontal path) or elevate to a higher level (the vertical path).

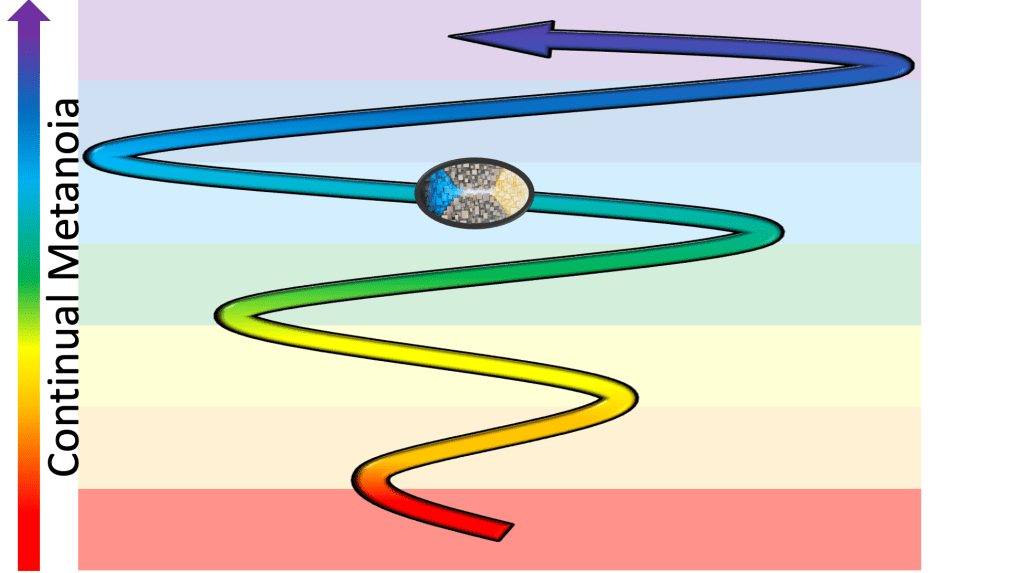

The Developmental Spiral

These three phases follow a predictable sequence that creates not a circle but a spiral of development:

- Every contrast creates potential for tension

- Every tension creates potential for resolution

- Every resolution creates potential for a higher-level contrast

When we complete this cycle, we don’t return to where we started but advance to a new level where we encounter more sophisticated forms of contrast. Each level encompasses greater breadth and depth than its predecessor, becoming more inclusive and expansive.

The Tripolar Self and the Law of Three

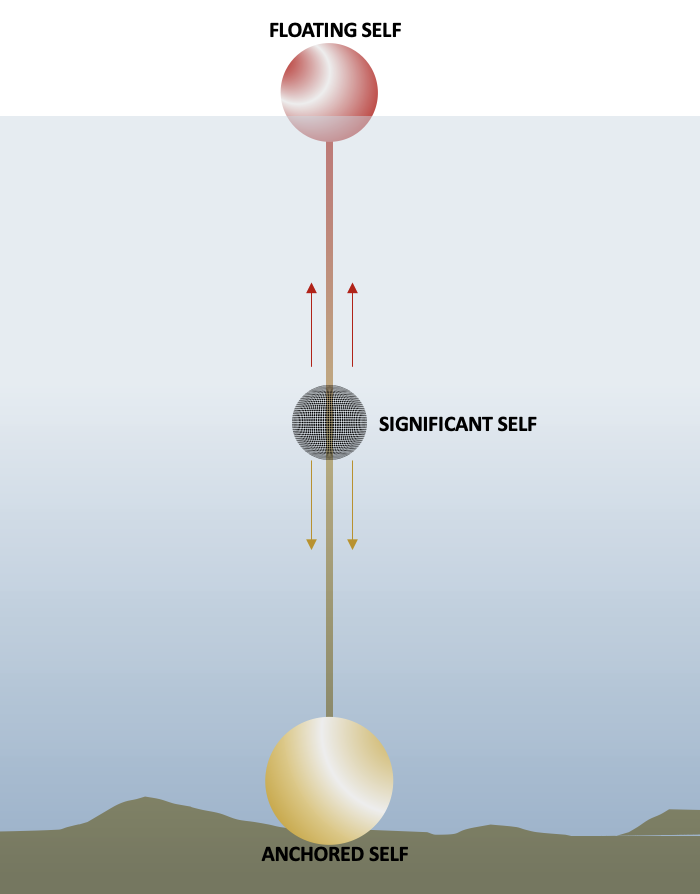

My framework of the Tripolar Self represents a practical application of the Law of Three to the journey of psychological and spiritual development. The three elements—Anchored Self, Floating Self, and Significant Self—interact in ways that create the conditions for transformation.

The Significant Self: The Agent of Transformation

At the center of this framework is what I call the “Significant Self”—our sense of self that operates in the world and makes meaning of our experiences. The term “significant” refers to this self’s function as the meaning-maker, interpreting each moment’s catalysts as they enter our awareness. This is the agential self, the one with choice and volition, capable of moving between different modes of being.4

The Significant Self constantly oscillates between two depths: the Floating Self above and the Anchored Self below. Its position along this vertical axis determines how we perceive reality, relate to others, and respond to life’s challenges. The journey of transformation involves learning to position our Significant Self more consistently within the depth of the Anchored Self, rather than remaining trapped in the perspective of the Floating Self.

The Floating Self: The First Position

The Floating Self corresponds to what Rohr calls the “false self.” It operates from a rigid, narrow, and fragile perspective, constantly seeking validation, status, and control. This self is preoccupied with appearances, achievements, and maintaining a carefully curated image. As Rohr describes it, the Floating Self believes “it’s greatly important to be important,” making it “constantly offended” and defensive.5

The Floating Self’s ethos is “transcend and exclude.” It attempts to elevate itself by diminishing others, believing “I’m better than you because I’m more spiritual,” which inevitably leads to separation and “othering.”6 There is a sense of of transcending a former worldview, arriving into a new advanced stage, and then excluding all former stages as less than. This self creates boundaries between “us” and “them,” constantly sorting people into categories of worthiness. As both the late Trappist, Fr. Thomas Keating, OCSO7,8, and Rohr have taught in various occasions, the Floating Self pursues power, prestige, and possessions in order to aggrandize social positioning for its own sake. The Floating Self is not bad nor evil, but it is very dangerous when we mistake our Floating Self for our Anchored Self.

Most people live primarily from their Floating Self unless they develop awareness of this pattern. Interestingly, the Floating Self isn’t something to eliminate—it belongs to our human experience and can even be utilized by the Anchored Self to accomplish good in the world. The problem isn’t having a Floating Self but being unconsciously identified with it.

The Anchored Self: The Third Position

The Anchored Self represents what Rohr calls the “true self”—who we really are at our deepest levels, beneath all identities and roles. I call it “anchored” because it’s grounded in reality rather than illusion, connected to what Rohr describes as “the isness of you,” the essential beingness that precedes all constructed identities.9 The Anchored Self is anchored in the Ground of Being and, in fact, is the Ground of Being10 come to an individuated nodal point.

Living from the Anchored Self brings depth and freedom from egoic needs. From this place, life is no longer about “me” but about doing good using whatever means are available, without taking ownership of successes or failures. Its ethos is “include and transcend”—incorporating all aspects of experience, including what we might consider imperfections, into a larger, more spacious understanding.11

The Anchored Self understands wholeness not as perfection without blemish but as a reality that incorporates our shadow sides, our wounds, and our limitations. These perceived imperfections are honored because they become catalysts for growth. Transcending from this perspective involves including all of one’s shadow side and also including others’, allowing for transcendence through spaciousness rather than exclusion.

The Law of Three in Psychospiritual Development

When we apply the Law of Three to the movement between the Floating Self and the Anchored Self, we can map the developmental process more clearly:

- Contrast: The initial phase occurs when we recognize the disparity between our Floating Self (who we think we are) and glimpses of our Anchored Self (who we truly are). This contrast might come through spiritual practices, relationships, or life experiences that reveal the limitations of our ego structure.

- Tension: As this awareness grows, it creates tension. Our Significant Self experiences the pull between the familiar security of the Floating Self and the authentic freedom of the Anchored Self. This tension manifests as the discomfort of cognitive dissonance, emotional ambivalence, or spiritual restlessness.

- Resolution: Transformation occurs when we allow this tension to resolve not through regression to the Floating Self nor through rejection of it, but through integration. The Significant Self descends to the level of the Anchored Self, which then can compassionately include and utilize the Floating Self without being identified with it.

This process doesn’t occur once but repeatedly throughout life, creating a developmental spiral. Each resolution creates the conditions for a new level of contrast, as we encounter more subtle forms of ego attachment and deeper dimensions of authentic being.

Transformation Through Falling Upward

Richard Rohr’s concept of “Falling Upward” complements this understanding by highlighting how the descent of the Significant Self toward the Anchored Self often requires what feels like failure or falling. As Rohr describes, spiritual maturity comes through what initially appears as “falling” but ultimately propels us toward greater wisdom and depth.12

In the first half of life, we necessarily focus on establishing our identity, building what Rohr calls our “container” or ego structure. This involves creating boundaries, learning social norms, establishing ourselves professionally, and developing discipline. During this phase, the Significant Self primarily operates from the perspective of the Floating Self, which is appropriate and necessary for early development.

However, the transition to the second half of life involves a fundamental shift. Rather than continuing to build and defend the ego structure, we begin to question its limitations and move beyond dualistic thinking. This transition rarely happens smoothly—it typically requires some form of “falling” or failure, which Rohr sees not as unfortunate obstacles but as necessary catalysts for spiritual growth.13

I’ve observed that clients who have experienced significant setbacks—loss of status, relationship failures, health crises, or professional disappointments—often stand at the threshold of their greatest transformation. These experiences can crack open the Floating Self’s carefully constructed narrative, creating space for the Significant Self to descend toward the Anchored Self.

Living from Different Aspects of Self

Life in the Floating Self

When the Significant Self is primarily positioned within the Floating Self, life becomes a constant struggle for validation and control. I’ve witnessed this pattern in many clients—executives who derive their entire sense of worth from their professional achievements, parents who live vicariously through their children’s successes, spiritual seekers who use their practices as badges of superiority rather than tools for authentic transformation.

A person operating primarily from the Floating Self might:

- Become defensive when receiving feedback, unable to distinguish between their actions and their worth

- Feel threatened by others’ successes, viewing life as a zero-sum game

- Judge themselves and others harshly, creating rigid categories of right and wrong

- Experience anxiety when their carefully constructed image is challenged

- Seek constant external validation through achievements, appearances, or affiliations

- Feel empty despite outward success, wondering “is this all there is?”

- Use spiritual practices to enhance their ego rather than transcend it

One client, a successful attorney, came to me after a panic attack in the courtroom. Despite her impressive career, she lived in constant fear of being “found out” as inadequate. Her Significant Self was so deeply embedded in her Floating Self that any professional challenge became an existential threat. Our work involved helping her recognize this pattern and gradually create space between her core self and her professional identity.

Life in the Anchored Self

When the Significant Self operates more consistently from the Anchored Self, life takes on a different quality. There’s a groundedness that persists even amidst challenges, a capacity to hold paradox and complexity without being overwhelmed.

A person living more from their Anchored Self might:

- Receive criticism with openness, able to learn without feeling diminished

- Celebrate others’ successes genuinely, recognizing abundance rather than scarcity

- Hold strong values while remaining compassionate toward different perspectives

- Feel comfortable with vulnerability and imperfection

- Find motivation from within rather than seeking external validation

- Experience a sense of purpose that transcends personal achievement

- Use spiritual practices as tools for service and compassion rather than self-enhancement

Another client, a teacher who had survived cancer, demonstrated this shift dramatically. Before her illness, she had been consumed with proving her worth through perfect performance. After recovery, she found herself operating from a deeper place—still excellent in her work but no longer defined by it. “I realized I’m not my achievements,” she told me. “There’s something more essential that cancer couldn’t take away.” Her Significant Self had found its home in the Anchored Self, allowing her to live with greater freedom and authenticity.

The Journey Downward: Great Love, Great Suffering, and the Law of Three

The movement of the Significant Self from the Floating Self toward the Anchored Self follows the pattern of the Law of Three—requiring contrast, tension, and resolution. This developmental process is facilitated by what Rohr identifies as the two great catalysts for transformation: Great Love and Great Suffering.14

The Vulnerability of Love and Suffering

Great Love and Great Suffering function as the primary catalysts for contrast and tension in our spiritual development. Great Love reveals our fundamental interconnection with others, while Great Suffering exposes the limitations of our individual control. Both experiences challenge the Floating Self’s illusion of separateness and self-sufficiency.

When we truly love, we relinquish control, allowing ourselves to be seen, known, and affected by another. This vulnerability—this willing surrender of our defenses—creates an opening through which we can glimpse our Anchored Self. Similarly, when we suffer significant losses or disappointments, we encounter the limits of our control. The Floating Self, which operates on the illusion of autonomy, cannot integrate these experiences of powerlessness.

Leonard Cohen captured this dynamic perfectly in his song “Anthem” when he wrote: “Ring the bells that still can ring; Forget your perfect offering; There is a crack, a crack in everything; That’s how the light gets in.”15 This insight—that our wounds and failures become the very openings through which transformation enters—reveals the paradoxical nature of spiritual growth. Our imperfections, limitations, and suffering are not obstacles to overcome but doorways through which we access deeper realities.

The Power of Powerlessness

What makes both Great Love and Great Suffering so transformative is that they place us upon the crosses of our powerlessness. When we truly love another person, we cannot control their response. When we face serious illness or loss, we cannot control the outcome. In these moments, the Floating Self—built on control and management of our image—has no answers. It falls apart.

This falling apart, this experience of powerlessness, is precisely what initiates the tension phase of the Law of Three. In the space created by the Floating Self’s inadequacy, we may discover the Anchored Self waiting beneath our constructed identity. This is the reconciling force in the Law of Three—neither clinging to control (affirming) nor being destroyed by its absence (denying), but discovering a deeper identity beyond both.

How Great Love Is a Form of Great Suffering

When we understand suffering as experiencing vulnerability in moments when we desire control but find ourselves powerless, we can see how Great Love is itself a form of Great Suffering. To love fully requires us to surrender our defenses, expose our hearts, and accept that we cannot manage the outcome. The Floating Self, which seeks safety through control, experiences this vulnerability as threatening.

This explains why many people unconsciously limit their capacity to love—because love requires a willingness to suffer. To open ourselves fully to another person means accepting the possibility of rejection, disappointment, or loss. The Floating Self seeks to avoid these risks, but the Anchored Self recognizes that the capacity to remain open despite uncertainty is precisely what gives life its depth and meaning.

I’ve observed that clients who embrace both love and suffering as teachers, rather than seeking love while avoiding suffering, make the most significant shifts in their sense of self. They learn to welcome vulnerability rather than defend against it. When we can stand in our powerlessness without needing to escape it—whether that powerlessness comes through love or through loss—we discover a strength that isn’t based on control but on connection to something deeper and more enduring than our constructed identity.

Resolution: The Transformation of the Floating Self

The resolution phase of the Law of Three involves not the elimination of the Floating Self but its transformation. As our Significant Self aligns more consistently with the Anchored Self, we don’t reject our constructed identity but relate to it differently. The Floating Self becomes a tool rather than our identity, something we use rather than something we are.

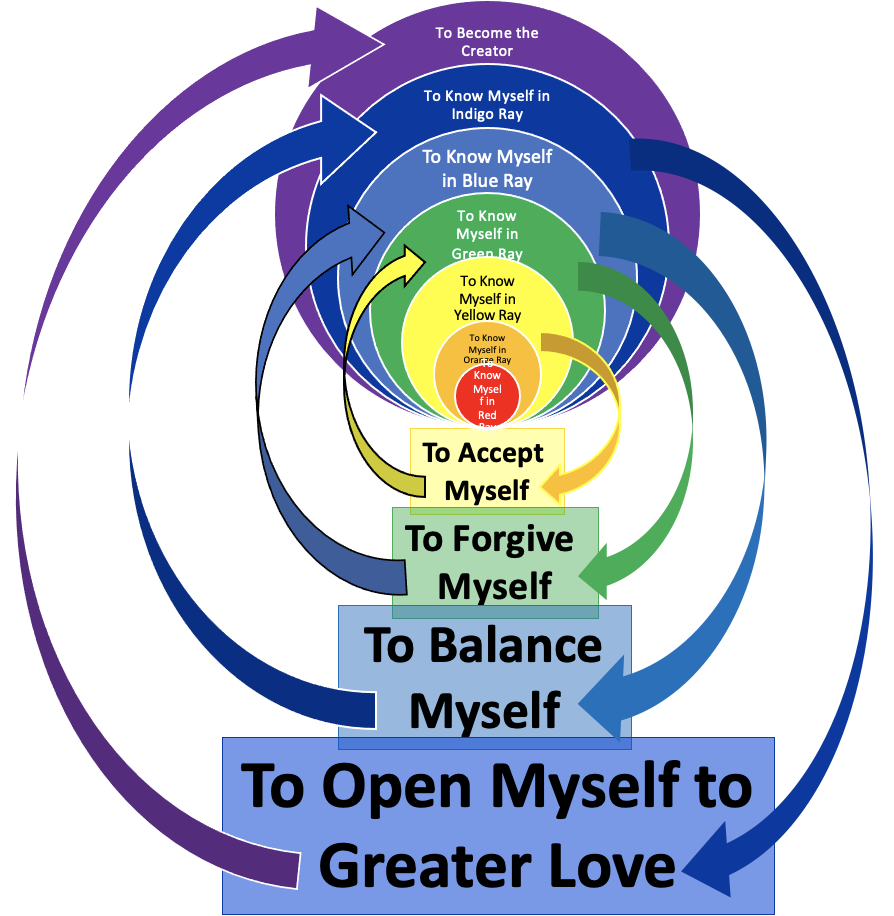

This transformation follows the resolution process outlined in the Law of Three:

- Accepting the contrast: Acknowledging the reality of the difference between our Floating Self and our Anchored Self without attempting to eliminate either

- Acknowledging the tension: Recognizing and feeling the dynamic energy created by living in the space between these two aspects of self

- Balancing oneself: Finding equilibrium amidst these competing forces without being pulled entirely into one or the other

- Choosing to release the identity formed at the previous level: Letting go of exclusive identification with the Floating Self

- Opening oneself to greater love: Expanding our capacity for integration and harmony through the spaciousness of the Anchored Self

Through this process, the Floating Self is not eliminated but redeemed. It becomes a vehicle through which the Anchored Self can express itself in the world, offering its unique gifts and abilities in service rather than in pursuit of validation. This is the essence of what Rohr calls “falling upward”—the ego falls from its position of dominance only to be reclaimed and utilized from a place of greater depth and integration.

Conclusion

The goal of a fully lived life is not the pursuit of happiness but rather the discovery of meaning and purpose. Emotions like happiness and sadness come and go—they are appropriate and belong to the whole human experience, but they are not teleological. They are not the end goal of human existence.

What characterizes a life well-lived is not perpetual happiness but an abiding deep feeling of joy that emerges from wholeness manifested both within and without. This joy creates a luminosity that emanates from internal integration and can illuminate others, drawing them toward their own Anchored Selves.

The ultimate goal of life, as I’ve come to understand it, is to learn how to die well and often—to surrender repeatedly down into the Anchored Self and then to use the Floating Self to do good in the world. Through this process, the Floating Self becomes redeemed and sanctified. It is transformed from a source of separation into a vehicle for service.

The framework of the Tripolar Self, understood through the lens of the Law of Three, offers a map for understanding our internal landscape and the journey of transformation. By recognizing where our Significant Self is operating from in any given moment, we gain the capacity for choice rather than remaining unconsciously identified with the Floating Self.

My work as a psychospiritual therapist involves helping clients recognize these patterns in themselves, develop self-compassion for their Floating Self’s strategies of protection, and gradually learn to center their Significant Self in the depth and spaciousness of the Anchored Self. This journey isn’t about achieving perfection but about growing in awareness, authenticity, and love through the ongoing spiral of contrast, tension, and resolution.

As Richard Rohr states, “Within us there is an inner natural dignity… an inherent worthiness that already knows and enjoys… an immortal diamond waiting to be mined.”16 My greatest privilege is accompanying others as they discover this diamond within themselves—their Anchored Self—and learn to live from that place of wholeness, freedom, and love.

Endnotes

- My writing on the perennial tradition and its integration with contemporary spiritual thought can be found at http://www.cosmicchrist.net, where I explore the synthesis of conventional wisdom with esoteric sources. ↩︎

- Further information about my practice and approach can be found at http://www.dougscottcounseling.com. ↩︎

- Richard Rohr, OFM, founded the Center for Action and Contemplation in 1987. More information can be found at http://www.cac.org. ↩︎

- This concept of the Significant Self as the meaning-making aspect of consciousness draws from both Rohr’s work and developmental psychology, particularly the theories of Robert Kegan on meaning-making systems. ↩︎

- Richard Rohr, Immortal Diamond: The Search for Our True Self (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2013), 56. ↩︎

- Ibid., 58. ↩︎

- https://www.contemplativeoutreach.org/fr-thomas-keating/ ↩︎

- Thomas Keating, The Human Condition: Contemplation and Transformation (Paulist Press, 1999). “The false self is looking for fame, power, wealth, and prestige. The unconscious is very powerful until the divine light of the Holy Spirit penetrates to its depths and reveals its dynamics. Here is where the great teaching of the dark nights of St. John of the Cross corresponds to depth psychology, only the work of the Holy Spirit goes far deeper. Instead of trying to free us from what interferes with our ordinary human life, the Spirit calls us to transformation of our inmost being, and indeed of all our faculties, into the divine way of being and acting.” ↩︎

- Ibid., 82. ↩︎

- https://religiousnaturalism.org/god-as-ground-of-being-paul-tillich/ ↩︎

- This “include and transcend” pattern aligns with Ken Wilber’s concept of development as a process of transcending and including rather than rejecting previous stages, which Rohr references in his work. ↩︎

- Richard Rohr, Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2011), 12. ↩︎

- Ibid., 65-66. ↩︎

- This phrase appears frequently in Rohr’s teachings, though not always in print. It encapsulates his understanding that transformation happens not through willpower but through our response to love and suffering. ↩︎

- Leonard Cohen, “Anthem,” from the album The Future (Columbia Records, 1992). ↩︎

- Richard Rohr, Immortal Diamond, 56. ↩︎